Until around the 1960s, before mass production of steel products became widespread for consumer use, it is said that there was a blacksmith in every town, which makes perfect sense. This is something I wasn't aware of, as I have no recollection of ever seeing blacksmiths in my area.

That being said, older generations, including myself, are all familiar with a song called “Village Blacksmith”, which was often practiced in chorus during music class in elementary school. This Ministry of Education-approved song, likely introduced as part of the government's effort to instill values of diligence and hard work, had been cherished by children since 1912. The song was removed from the elementary school music curriculum in 1977, coinciding with the rise of accelerated industrialization and the shift away from manual labor.

Lyrics

Without pausing for a moment, the sound of hammering echoes, Sparks scatter, hot drops of water fly, Even the wind of the bellows doesn't catch its breath, Diligently working, the village blacksmith.

The master is a renowned old man of the village, Unaffected by the ailments of early rising and early sleeping, His arms harder than iron, Victory lies in his resolute heart.

No longer swords, but scythes, sickles, horse drawn hoes, hoes, spades and hatchets, Forging amidst the peace, never resting, Daily battling against the enemy of idleness.

Earning a living, free from poverty, The famous blacksmith thrives day by day, Unrivaled in the neighborhood, praised for his work, The sound of hammering echoing even higher.

The lyrics shed light on blacksmiths’ heritage, their dedication, and their social standing. Though the number of blacksmiths declined significantly ever since, the blacksmith tradition still continues in different parts of Japan to this day, with some remaining in the exact same form for generations serving mainly for the local community while others reinvent themselves and expand their reach overseas.

Blacksmiths are broadly classified into three categories: "Okaji" (literally meaning "big smith" in Japanese), who are engaged in ironmaking, "katana-kaji" or swordsmiths, known as "Kokaji" (small smith), and "No-kaji" (field smith) or village blacksmiths, who handle knives, agricultural tools, fishing gear, and forestry blades.

Most village blacksmiths are small-scale operations run by families or master craftsmen and their apprentices. To serve the local community, they custom-make tools tailored to the specific needs of their customers and the local environment — whether it be the type of soil in the farmland or the trees grown in the area.

These blacksmiths are highly skilled in shaping iron freely based on their experience, taking into consideration the users and their specific applications. Rather than relying on detailed plans or blueprints, they follow a mental blueprint formed through years of practice and mastery of their craft.

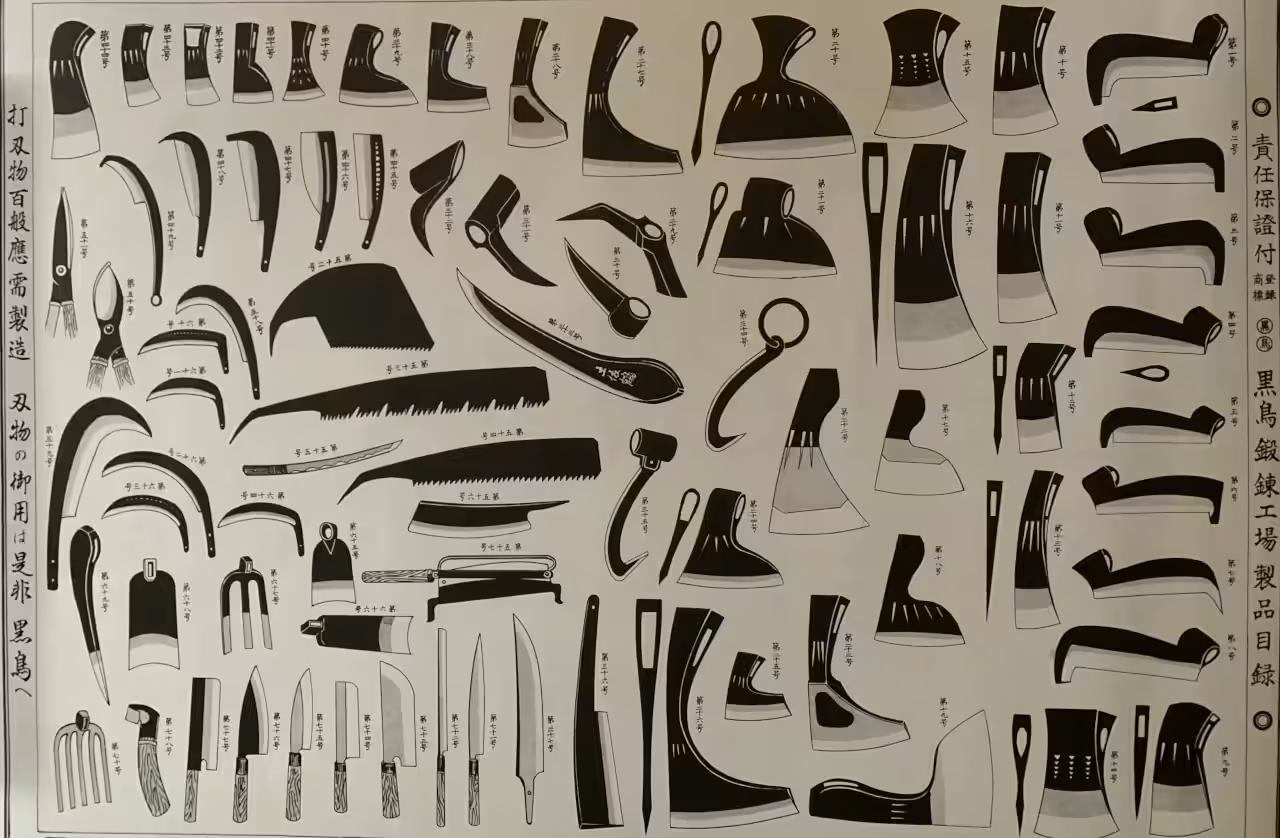

Various forged products offered by a village blacksmith in Tosa

Various forged products offered by a village blacksmith in Tosa

Blacksmiths continue to uphold the time-tested traditional techniques and disciplines shaped by countless trials and errors passed down from generation to generation. This tradition can be traced back, directly or indirectly, to Tatara ironmaking, which began around the sixth century, and the later development of Samurai sword-making.

Carefully hand-crafted blades are not just about getting the job done; to me, they possess a sense of functional beauty that inspires a lifetime of appreciation and care.

Blade made out of Aogami Blue #2 steel

Blade made out of Aogami Blue #2 steel

I recall owning a hatchet with a red plastic handle, which I used to split wood logs for the furnace during the freezing winters in New Jersey. The handle eventually broke off, and I purchased a replacement from a nearby chain hardware store. Looking back, I wish I had discovered this cultural aspect sooner — tasks like those would have been far more enjoyable with a beautiful, handmade hatchet.

Handheld hatchet with oak handle crafted by Kurotori, Tosa

Handheld hatchet with oak handle crafted by Kurotori, Tosa